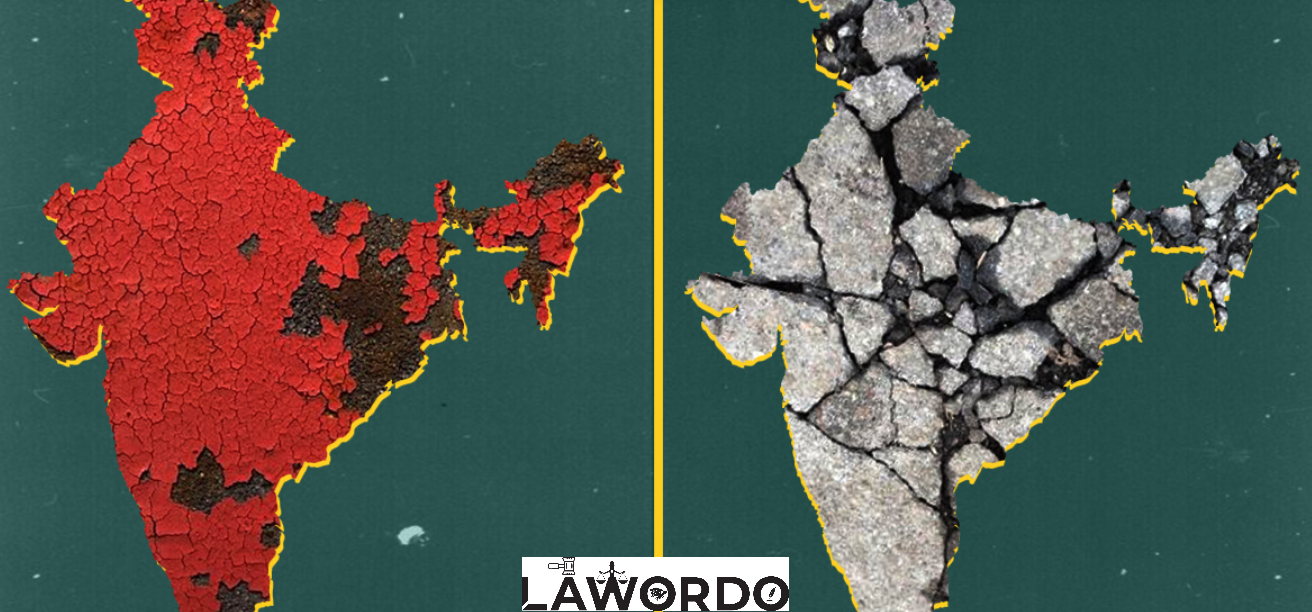

This #10YearChallenge should make India feel ashamed !

Over the past few days, the #10YearChallenge meme on social media urged people to post their 2009 selfies alongside their 2019 ones. Most people were interested in how they and other people had grown; while some posted snippets of how their life had changed from 10 years ago.

Now imagine if you did this for India.

Contrast numbers and you’ll feel good. On an average, an Indian earned around $1250 in the year 2009. Today they earn around $2,000.

Every third Indian was living below the poverty line a decade ago. Today, that number is lower than one in five. In other words, the income of millions of Indians has considerably improved in the 10 years. The number of internet users in the country has grown 10 times, from around 50 million in 2009 to around 500 million.

So, the good is increasing and the bad is slowing. There are major exceptions to this: new jobs are not growing and pollution is not slowing— but hey, going by the numbers alone, we’re looking pretty good in the #10YearChallenge.

While individual Indians seem to have done well over the past decade, India is more or less where it was. Worse, politics and policy priorities seem to have relapsed to 1989.

Rural suffering hasn’t changed much: better phones, better roads, and better vehicles have merely stopped the situation from going far worse. Our cities haven’t improved either. Sure, there were some schemes like JNNURM and the Smart Cities Mission, several new airports—a few comparable to the best in the world—have been built, but our cities look as dilapidated as before.

Behind, around and seldom right in front of a shiny new glass-and-concrete office park or shopping mall are narrow, dusty old streets and shanty towns. There is more traffic on the same old streets as more people can afford cars and are forced to use them because public transport is in bad shape.

There is more parking on the same old roads; people have nowhere else to park their vehicles. I could ride a bicycle to school in 2009; my kids can’t in 2019.

If our enduringly overcrowded, ever-sprawling, grimier cities cut a sorry figure in the #10YearChallenge, they are merely symptoms of a wider malaise: no one is interested in fixing any of India’s systemic, structural problems.

One reason or the other—and there are plenty— is cited to laugh at you for even inferring that we need quantum leaps, not anemic, reluctant, tentative, incremental changes that try to hold together a collapsing edifice with used cello tape, as it were.

The Narasimha Rao-Manmohan Singh reforms of 1991 made us forget the series of injuries that India suffered from 1989 to ’92. It represented the first real quantum jump in the country. It’s not just that the economy started growing. Things changed structurally. India opened up to the world. We then spent the 1990s stealthily defending economic liberalization and assuring the world, but mostly ourselves, that the ‘reforms were irreversible’.

By 1999, it was generally understood that the reform process must be taken forward, and the narrative of ‘we need second-generation reforms’ was in the air. The Vajpayee government initiated a few policy changes—telecom and highways come to mind—in this direction, but it either wouldn’t or couldn’t make another quantum leap.

The economy grew, but India didn’t change.

By the end of the first Congress-led United Progressive Alliance government, the need for a big second economic liberalization began to run ‘into the dreary desert sand of dead habit.’

The Communists would not allow it, while the Congress tied itself into knots with agendas like social justice, inclusive growth and so on. Big govt. schemes were in; the biggest political priority and certainly the larger national narrative seemed to be the creation of state-sponsored, state-administered social safety nets, while we forgot about those second-generation reforms.

The economy continued to grow, but India didn’t change.

Then, when he was still a prime ministerial candidate, Narendra Modi spoke to Indians’ aspirations. Many of his campaign ideas suggested that he intended to bring about another fundamental break, but once in power he too carried on as his predecessors did: more government schemes, more allocations, more programmes.

Worse, the BJP’s well-resourced propaganda machine and its many partisans among the public claimed that whatever the Modi government did was big bang reform, only our biases didn’t allow us to see this fact.

Others contended that Modi discovered that big bang reforms were not possible after Rahul Gandhi accused him of running a ‘suit-boot sarkar’ that benefited the rich.

So in 2019, we are back to farm loan waivers, increased allocations under NREGA demands for ‘special status’ and new quotas and reservations. Not just that, increasing mobilization of Indians for building a Ram Temple at Ayodhya reminds us of 1989.

Arun Shourie was on a crusade against tyranny then; he’s on one now. And, in 2019, we have a constellation of regional leaders holding hands in massive political rallies. In many ways, it’s 1989 all over again.

That’s sad. It’s almost as if we’re beating our aspirations to death with the hammer of our own bitterness. We’ve forgotten about reforms; we’ve forgotten about liberalization; we’ve even given upholding the government accountable.

#10YearChallenge is a good occasion to remember what we’ve forgotten.

So let me say this: we should be disgusted with our shoddy cities, not adjust to them. We should be embarrassed that we are nowhere close to addressing rural distress, nowhere close to creating adequate jobs, cows take up so much of our collective bandwidth and business houses can still twist government policies in their favor.

We should keep our expectations high, and not be fooled into settling for less.

Economic growth is necessary, but what we do with the additional resources it puts in our hands is more important.

A caterpillar that perpetually grows is a grotesque freak: becoming a butterfly requires a metamorphosis.