THE BHOPAL DISASTER – CRITICAL ANALYSIS

AUTHORED BY: SANAH SETHI

AMITY LAW SCHOOL (L.L.B 3 YEARS)

INTRODUCTION

The Bhopal disaster has raised complex legal questions about the liability of a parent company for the act of its subsidiary, the responsibility of multinational corporations engaged in hazardous activities and the transfer of hazardous technology. On the night of 2-3 December 1984, the most tragic industrial disaster in history occurred in the city of Bhopal. Union Carbide Corporation (UCC), an American Corporation with subsidiaries operating throughout the world, was running one of its subsidiary, Union Carbide India Limited (UCIL), a chemical plant in Bhopal. The plant was situated in the northern sector of the city having hutments adjacent to it on its southern side which was occupied by impoverished squatters. The chemical plant manufactured pesticides called Sevin and Temik. Methyl isocyanate (MIC), a highly toxic gas, is an ingredient used in the production of both Sevin and Temik. On the night of the tragedy, MIC leaked from the plant in substantial quantities and the prevailing winds blew the deadly gas into the overpopulated hutments adjacent to the plant and into the most densely occupied parts of the city. The massive escape of the lethal MIC gas from the Bhopal plant into the atmosphere rained death and destruction upon the innocent and helpless persons and caused widespread pollution to its environs in the worst industrial disaster mankind has ever known. It is estimated that 2660 persons lost their lives and more than two lakh persons suffered injuries-some serious and permanent-some mild and temporary. Livestock was killed and crops damaged. Businesses were interrupted. A noticeable feature of the case is that the UCIL was incorporated in India and 50.99% of its stock was owned by the UCC. On 7 December 1984, the first lawsuit was filed by American lawyers in the US on behalf of thousands of Indians. Since then 144 additional actions have commenced in federal courts in the US. All these actions were consolidated.

BHOPAL GAS LEAK DISASTER ACT, 1985

On 29 March 1985, the Government of India enacted legislation, the Bhopal Gas Leak Disaster (Processing of Claims) Act, 1985, providing that the Government of India has the exclusive right to represent Indian plaintiffs, in connection with the tragedy. The Act also directed the Indian Government to organize a plan for the registration and processing of the claims of victims. Pursuant to the Bhopal Act, the government of India on 8 April 1985 sued the UCC in the US District Court for relief. The Indian government preferred the American court due to several reasons. First, the Indian Government did not have confidence in her own judicial system. Secondly, the Indian government apprehended that the UCC, an American Corporation, might not surrender to the Indian judicial process. Thirdly, the Indian government thought that the American court would award higher damages in comparison to the Indian courts. It is interesting to note that the Indian government did not make the UCIL even a co-defendant and fastened exclusive liability on the multinational, UCC, which held 50.9% of the shares in the UCIL. Judge John F. Keenan of the US District Court dismissed the Indian consolidated case on the ground of forum non-conveniens and declared that Indian court was the convenient and appropriate forum. However, the District Judge Keenan imposed three conditions on the defendant UCC in its order. Against the decision of the District Court, 145 individual plaintiffs filed an appeal in the US Court of Appeals. The defendant UCC also filed a cross-appeal in the US Court of Appeals. The Court of Appeals dismissed the appeal of the individual plaintiffs and found nothing wrong with the District Court has dismissed the consolidated claims of the plaintiffs on grounds of forum non-conveniens. However, the Court of Appeals allowed partly the cross-appeal of the defendant UCC by deleting the second condition and modifying the third one imposed by the District Court. On 14 February 1989, the Supreme Court of India came out with an overall settlement of the claims and awarded US$ 470 million (Rs 715 crores) to the Government of India on behalf of all the Bhopal victims in full and final settlement of all the past, present and future claims arising from the Bhopal Gas leakage. The Supreme Court also terminated all the civil, criminal and contempt of court proceedings against the corporate officials pending in the Indian courts. In December 1989, the Supreme Court upheld the constitutional validity of the Bhopal Act which conferred an exclusive right on the Government of India to represent all Bhopal victims not only in the Indian but even foreign courts. The review petitions under Article 137 and writ petitions under Article 32 of the Constitution of India were filed against $470 million settlement which raised fundamental issues as to the constitutionality, legal validity, propriety and fairness of the settlement of the claims of the victims in a mass-tort action. In its order dated 3 October 1991, the Supreme Court upheld the US $470 million settlement recorded by the court while hearing the appeal arising out of interlocutory order passed in the suit. However, the Supreme Court had set aside its earlier order quashing the criminal proceedings against the corporate officials.

BHOPAL GAS DISASTER CASE ADJUDICATION IN INDIA

In Union of India v. Union Carbide Corporation, during the pendency of the appeals filed by both the parties in the Court of Appeals in the US, the Union of India filed a suit for damages on 5 September 1986, in the District Court of Bhopal. On 17 November 1986, upon the application of the Union of India, the District Court of Bhopal granted a temporary injunction restraining the UCC from selling assets, paying dividends or buying back debts. On 27 November 1986, the UCC gave the undertaking to preserve and maintain unencumbered assets of US $ 3 million. On 30 November 1986, the District Court, Bhopal lifted the injunction against the Union Carbide selling assets on the basis of the written undertaking by UCC to maintain unencumbered assets of US $3 million. On 16 December 1986, the UCC filed a written statement contending that they were not liable on the ground as they had nothing to do with the Indian company and they were a different legal entity which never exercised any control. On 2 April 1987, the District Court, Bhopal made a written proposal to all parties for considering reconciliatory interim relief to the gas victims. In September 1987, the UCC and the Government of India sought time from the Court of District Judge, Bhopal, to explore avenues for settlement. However, in November 1987, both the Indian government and the UCC announced that settlement talks had failed and the District Judge Deo extended time. On 17 December 1987, the District Judge Deo ordered interim relief amounting to Rs 350 crores. The defendant UCC was directed to deposit the amount within two months from the date of the said order. Being aggrieved thereby, the UCC filed a civil revision petition. On 4 February 1988, the Chief Judicial Magistrate of Bhopal ordered notice for a warrant on the UCC for a criminal case filed by the CBI against the UCC and its various officials. The charge sheet was under Sections 304, 324, 326, 429 IPC. It charged the UCC by saying that the MIC gas was stored and handled in stainless steel vessels which was never done. The charge-sheet stated that a scientific team headed by Dr. Varadarajan had concluded that the factors which had led to the toxic gas leakage causing heavy toll existed with the unique properties of very high reactivity, volatility and inhalation toxicity of the MIC. It was further stated in the charge-sheet that the needless storage of large quantities of the gas in very large sized containers for inordinately long periods as well as insufficient caution in design and materials of construction and in provision of measuring and alarm instruments, together with the inadequate controls on systems and quality of storage and stored material as well as lack of necessary facilities for quick effective disposal of material exhibiting instability, led to the accident. It also charged that the MIC was stored in a negligent manner and the local administration was not informed, inter alia, of gases produced by its reaction and the medical steps, were not taken immediately. It was further stated that apart from the design defects, the UCC did not take any adequate remedial action. It was further alleged that various other acts of criminal negligence were also committed. The UCC then filed a revision petition in the Madhya Pradesh High Court under Section 155 CPC, against the order of the Bhopal District Court in a claim for damages made by the Union of India under the Bhopal Gas Leak Disaster (Processing of Claims) Act, 1985, on behalf of all the claimants. Justice Seth delivered the judgment on 4 April 1988. The defendant UCC felt aggrieved by the direction of the District Judge Deo to deposit within a period of two months a sum of Rs 350 crores by way of interim payment to be disbursed by the Commissioner appointed under the Bhopal Act of 1985 for granting substantive relief to the victims of the disaster. The case before the Madhya Pradesh High Court involved three main issues:

- Whether the enterprise [whichever it may be, the Indian enterprise (UCIL) or the defendant UCC] engaged in the hazardous or inherently dangerous activity at the Bhopal plant resulting in the MIC gas disaster, was liable to pay compensation to the gas victims;

- Whether it would be permissible to grant relief of interim payment under the substantive law of torts;

- Which principles should govern the determination of the quantum of compensation?

LIABILITY UNDER GENERAL LAW OF TORT

On the issue of the liability of the alleged tortfeasor in the Bhopal suit, the decision of the Supreme Court in M.C. Mehta v. Union of India (Mehta case) provided an answer. The relevant facts giving rise to the Mehta case and the Bhopal Gas Disaster case were very much similar in nature. While the Mehta case involved the escape of an ultra-hazardous chemical substance, namely methyl isocyanate. In its magnitude, the Bhopal disaster was unprecedented and far exceeded the oleum gas incident in the Mehta case. Therefore, the principle of absolute liability without exceptions applied more vigorously to the Bhopal Gas Disaster case. In the Mehta Case, the Supreme Court laid down the rule of absolute liability without exceptions. According to the Supreme Court, where an enterprise is engaged in hazardous or inherently dangerous activity and harm results to anyone on account of an accident in the operation of such hazardous or inherently dangerous activity, for example from the escape of toxic gas, the enterprise is strictly and absolutely liable to compensate all those who are affected by the accident and such liability is not subject to any of the exceptions which operate vis-à-vis tortious principles of strict liability under the rule in Rylands v. Fletcher. The Supreme Court explained that the absolute liability of such an enterprise stems from its obligation to ensure that the hazardous or inherently dangerous activity in which it is engaged must be conducted with the highest standards of safety and if harm results on account of such activity, the enterprise must be absolutely liable to compensate for such harm and it would be no answer for the enterprise to say that it had taken all reasonable care and that harm occurred without any negligence on its part. The Supreme Court emphatically held:

If the enterprise is permitted to carry on the hazardous or inherently dangerous activity for its profit, the law must presume that such permission is conditional on the enterprise absorbing the cost of any accident arising on account of such hazardous or inherently dangerous activity. Justice Seth of the Madhya Pradesh High Court applied the principle of absolute liability without exceptions to the Bhopal Gas Disaster case and held that whichever was the enterprise engaged in the hazardous or inherently dangerous activity at the Bhopal plant resulting in the MIC gas leak disaster-whether it be the Indian company, i.e. UCIL or it be the defendant UCC, was liable to pay compensation to the gas victims.

RELIEF OF INTERIM PAYMENT-PERMISSIBILITY-On the issue of permissibility of the relief of interim payment, the Madhya Pradesh High Court referred to English law which permits the grant of interim compensation during the intervening period between the commencement of an action and its ultimate trial in a suit for damages based on a tort, causing exceptional hardships to the persons claiming such damages. Accordingly, the Madhya Pradesh High Court held that the order of interim payment of damages could be passed in favor of the plaintiff Union of India, for the benefit of gas victims only if the Union of India would obtain a judgment for substantial damages against the defendant UCC. To hold the UCC liable, the court confronted with the following issues: first, whether it was legally permissible to lift the corporate veil of the Indian company UCIL, so as to hold the defendant UCC, liable; secondly, in case it was legally permissible to lift the veil, whether there existed prima facie a strong case showing that it was, in fact, the defendant UCC, which had the real control over the enterprise in question at Bhopal so as to hold the UCC liable for the tort.

LIFTING VEIL OF THE INDIAN COMPANY-The UCC forcefully argued that the court could not fit the veil of the Indian company to hold it liable. The UCC submitted that at best the UCIL was its subsidiary but a parent company was a distinct legal entity and could not be held liable for the acts or omissions of its subsidiary. The High Court held that the veil of the company could be lifted and its real face could be seen in a case where the statute itself contemplated lifting the veil or in a case of fraud, improper conduct, tax evasion, enforcement of welfare measures relating to industrial workmen and any other similar case. In the present case, on equitable considerations, the High Court decided that the veil of the Indian company-UCIL, could be lifted and its real face could be seen because the case concerned mass disaster and involved the assets of subsidiary company which were utterly insufficient to meet the just claims of the innocent victims of the disaster. The court went on to observe that it would fail in its duty if it did not apply the “lifting the veil” doctrine in a case of the nature of Bhopal suit.

QUANTUM OF COMPENSATION-On the issue of quantum of compensation, Justice Seth of the Madhya Pradesh High Court referred to the “deep pocket” theory evolved by the Supreme Court in Mehta case wherein it was held that the measure of compensation in such cases must be correlated to the magnitude and capacity of the enterprise because such compensation must have a deterrent effect. The larger and more prosperous the enterprise, the greater must be the amount of compensation payable by it for the harm caused on account of an accident in the carrying on of the hazardous or inherently dangerous activity by the enterprise. The Madhya Pradesh High Court clarified that in the facts and circumstances of the Bhopal Gas Disaster case, it would be just and proper to grant relief of interim payment of damages only in respect of the claims arising out of deaths and personal injuries under the Bhopal Act of 1985. The claims relating to deaths and personal injuries have been divided into four categories:

1) death

2) total disablement resulting in permanent disability

3) permanent partial disablement and

4) temporary partial disablement.

The court pointed out that the UCC was a financially sound corporation having more than Rs 262 crores worth of insurance coverage. Thereafter, the court assumed that if the suit proceeded to trial, judgment would be passed in respect of the claims relating to deaths and personal injuries at least in the following amounts: Rs 2 lakhs in each case of death 2) Rs 2 lakh in each case of total permanent disability 3) Rs 1 lakh in each case of permanent partial disablement 4) Rs 50000 in each case of temporary partial disablement. However, the amount of interim payment of damages payable by the UCC in respect of each of the above mentioned four categories was held to be as follows:1) Rs 1 lakh in each case of death 2) Rs 1 lakh in each case of total permanent disablement 3) Rs 50000 in each case of permanent partial disablement 4) Rs 25000 in each case of temporary partial disablement. Justice Seth of Madhya Pradesh High Court finally fixed the total amount of interim compensation payable by the UCC at Rs 250 crores. Thus, the High Court reduced the amount of interim compensation from Rs 350 crores to Rs 250 crores. The court clarified that the said interim compensation amounted to a payment of damages under the substantive law of torts on the basis of the prima facie case having been made out in favor of the plaintiff. The court also ordered the defendant to pay Rs 10000 as costs of this revision to the plaintiff, Union of India. Justice Seth s judgment was followed by a mixed response. Upendra Baxi appreciated Justice Seth s judgment and felt that the judgment proved the fairness and maturity of the Indian judiciary to do justice. However, Divan and Rosencranz felt that the judgment would not be enforceable in the US where there was no experience with regard to interim payments. An examination of merits of the case by Justice Seth without trial, seemed to Divan and Rosencranz, amounts to a motion for summary judgment which would not be granted in the defense offered in this case. American judges, according to them, would almost certainly dismiss Justice Seth s decree as a denial of the due process.

RELIEF OF INTERIM PAYMENT-PERMISSIBILITY

On the issue of the permissibility of the relief of interim payment, the Madhya Pradesh High Court referred to English law which permits the grant of interim compensation during the intervening period between the commencement of an action and its ultimate trial in a suit for damages based on a tort causing exceptional hardships to the persons claiming such damages. Accordingly, the Madhya Pradesh High Court held that the order of interim payment of damages could be passed in favor of the plaintiff Union of India, for the benefit of gas victims only if the Union of India would obtain a judgment for substantial damages against the defendant UCC. To hold the UCC liable, the court was confronted with the following issues: first, whether it was legally permissible to lift the corporate veil of the Indian company UCIL, so as to hold the defendant UCC, liable; secondly, in case it was legally permissible to lift the veil, whether there existed prima facie a strong case showing that it was, in fact, the defendant UCC, which had the real control over the enterprise in question at Bhopal so as to hold the UCC liable for the tort.

LIFTING VEIL OF THE INDIAN COMPANY-The UCC forcefully argued that the court could not lift the veil of the Indian company to hold it liable. The UCC submitted that at best the UCIL was its subsidiary but the parent company was a legally distinct entity and could not be held liable for acts or omissions of its subsidiary. The High Court held that the veil of the company could be lifted and its real face could be seen in a case where the statute itself contemplated lifting the veil or in a case of fraud, improper conduct, tax evasion, enforcement of welfare measures relating to industrial workmen and any other similar case. In the present case, on equitable considerations, the High Court decided that the veil of the Indian company-UCIL, could be lifted and its real face could be seen because the case concerned mass disaster and involved the assets of subsidiary company which were utterly insufficient to meet the just claims of the innocent victims of the disaster. The court went on to observe that it would fail in its duty if it did not apply the “lifting the veil” doctrine in a case of the nature of Bhopal suit.

LEGAL VALIDITY OF BHOPAL GAS DISASTER (PROCESSING OF CLAIMS) ACT, 1985

In Charan Lal Sahu v. Union of India, the validity of the Bhopal Gas Disaster (Processing of Claims) Act, 1985 was challenged. The Supreme Court held:

The Act is constitutionally valid. It proceeds on the hypothesis that until the claims of the victims are realized or obtained from the delinquents, namely UCC and UCIL, by settlement or adjudication and until the proceedings in respect thereof continue the Central Government must pay interim compensation or maintenance for the victims. In entering upon the settlement in view of Section 4 of the Act, regard must be had to the views of the victims and for the purpose of giving regard to these, appropriate notices before arriving at any settlement were necessary. In some cases, however, post-decisional notice must be sufficient but in the facts and circumstances of this case, no useful purpose would be served by giving a post-decisional hearing and having regard to the fact that there are no further additional data and facts available with the victims which can be profitably and meaningfully presented to controvert the basis of the settlement and further having regard to the fact that the victims had their say or on their behalf their views had been agitated in these proceedings and will have further opportunity in the pending review proceedings. The Act was conceived on the noble promise of giving relief and succor to the dumb, pale, meek and impoverished victims of a tragic industrial gas leak disaster, a concomitant evil in this industrial age of technological advancement and development. The Act had kindled high hopes in the hearts of the weak and worn, weary and forlorn. The Act generated the hope of humanity. The implementation of the Act must be with justice. The court observed that justice had been done to the victims but it was also true that justice had not appeared to have been done. The Supreme Court treated that as great infirmity: partly due to the fact that the procedure was not strictly followed and also, partly because of the atmosphere that was created in the country. Attempts were made to shake the confidence of the people in the judicial process and also to undermine the credibility of the Supreme Court which was unfortunate. In the opinion of the Court, this was due to the misinformed public opinion and also due to the fact that the victims were not initially taken into confidence in reaching the settlement. The court observed:

The credibility of the judiciary is as important as the alleviation of the suffering of the victims. It is hoped that these types of adjudication will restore that credibility. Principles of natural justice are integrally embedded in our constitutional framework and their pristine glory and primacy cannot and should not be allowed to be submerged by the exigencies of particular situations or cases. The Supreme Court pointed out that the court must always assert the primacy of adherence to the principles of natural justice in such adjudication. However, at the same time, the Supreme Court observed that the principles of natural justice must be applied in a particular manner, in particular cases having regard to the particular circumstances. Therefore, the court reiterated that promises made to the victims and hopes raised in their hearts and minds could only be redeemed in some measure where attempts were made vigorously to distribute the amount realized to the victims in accordance with the scheme as indicated above. The court also reiterated that attempts should be made to formulate the principles of law for the guidance of the government and the authorities for granting permission to carry on trade, dealing with materials and things, which have dangerous consequences within sufficient specific safeguards especially in case of multinational corporations trading in India. The court further reiterated that the law relating to damages and payment of interim damages or compensation to the victims of this nature should be seriously and scientifically examined by the appropriate agencies. Bhopal Gas Disaster and its aftermath emphasized the need for laying down certain norms and standards for the government to follow before granting permissions or licenses for running industries dealing with materials of dangerous potentiality. Accordingly, the Supreme Court recommended:

The government should examine or have the problem examined by an expert committee as to what should be the conditions on which future licenses and/or permission for running industries on Indian soil would be granted and for ensuring enforcement indicated. The government should insist as a condition precedent to the grant of such license or permission, creation of a fund in anticipation by the industries to be available for the payment of damages out of the said fund in case of leakage or damage caused as a result of accident or disaster flowing from negligent working of such industrial operation or failure to ensure measures to prevent such occurrence. The basis for damages in cases of leakages and accidents should be statutorily fixed taking into consideration the nature of damages inflicted, the consequences thereof and the ability and capacity of the parties to pay.

The Supreme Court further stated that in Bhopal Gas Disaster, the Union of India could not be sued as such by some of the victims for keeping down the amount of compensation, so as to reduce its own liability as a joint tortfeasor. The court held:

Union of India is itself one of the entities affected by the gas leak and has a claim for compensation from the UCC quite independent of the other victims. Therefore, the Union of India is in the same position as the other victims and in the litigation with the UCC, it has every interest in securing the maximum amount of compensation possible for itself and the other victims. The court observed that the Bhopal Act and the scheme thereunder provided for an objective and quasi-judicial administration of the number of damages payable to the victims of the tragedy. The Supreme Court found no basis for the fear that the officers of the government might not be objective and might try to cut down the amount of compensation so as not to exceed the amount received from the UCC. The Supreme Court rejected the contention that if the Union of India and its officers were joint tortfeasors, the Union would not stand to gain by allowing the claims against the UCC to be settled for a less amount. On the contrary, the court stated that the Union of India would be interested in settling the claims against the UCC at as high a figure as possible so that its own liability as a joint tortfeasor (if made out) could be correspondingly reduced. Accordingly, the court held that there was no vitiating element in the legislation in so far as it had entrusted the responsibility not only of carrying on but also of entering into a settlement if thought fit.

MY VIEW ABOUT BHOPAL GAS DISASTER

The affected people had to be treated medically, families protected from economic ruin due to death or incapacitation of breadwinner, the toxic products still fuming in the campus removed totally, the culprits in the organization and in the supervisory role in the govt had to be sued, etc

The recent statement of the Ministry of External Affairs that the request for extradition of the owner of the Union Carbide India, from the US was made in 2003 nearly two decades after the fatal leak..!! There were already rumors doing rounds how the gent was ”helped” to leave India soon after the historic calamity!!

The fact that the govt agreed for a paltry compensation, delayed the investigation and service of the charge sheets for decades, diluted the sections under which the accused were charged, etc amply proves that the Centre was least sincere to render justice to the citizens in the historic industrial tragedy of our times.

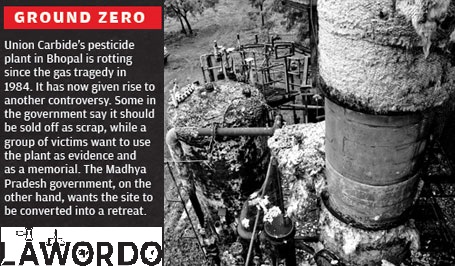

In the end, I would like to conclude by saying that the Bhopal Disaster has gone down in history as one of the world s worst industrial accident to ever occur. Thousands of people lost their lives, countless others injured and the environment contaminated due to numerous bad decisions among those who owned the plant. There are other several other industries working only for their own profit leaving the safety of people in it and around it in waters. The government should take necessary steps to control these industries so that no disaster occurs.